Should we not avoid that which remains out of the reach of our evaluation and shun it as not being of our species? As not truly or not yet human? And therefore to be handled with instinctive-animal kindness? Or with an indulgence that is paternalistically welcoming, with a view to some further integration into an already acculturated world? (Luce Irigaray, Key Writings, London: Continuum, 2004).

Within the vertical lines of genealogy and descent, what we term with far too much facility ‘the child’ is rendered in the neutral and functionalized as a form of property of the father by being separated from its original relation with the mother. This is, in more familiar terms, the oedipal triangulation of phallocentric kinship (see for instance Luce Irigaray, ‘Psychoanalytic Theory: Another Look,’ in This Sex Which is Not One, trans. by Catherine Porter and Carolyn Burke, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985, pp. 34-68). When the couple produces a child, they frequently lose their difference in its abstract oneness, while the child is in turn locked into a similarly abstract naturality by teleologies of development that demand nothing other than growing up into adulthood. From birth, the natural education of children aims at concealing their sexuate difference and assimilating them into the emptiness of the presumed universalized human subject, a masculine subject. Thus, as a product of strict genealogy, the child is only quantifiable through an equation of sameness to the adult, along degrees of resemblance and likeness, according to which it is always less than the adult, incomplete, unfinished, awaiting psychic acculturation.

The most illogical question to pose to Western culture regarding ‘the child,’ then, is how to relate to children with respect for their difference, as different from adults without being reducible to being measured against the latter. In what active ways does difference accrue inherently to the embodied forms that children take? How could that difference take its place in the relations of children to their adult others? Relations of genealogy cannot be willfully erased, to be sure, but the sexuate and horizontal relations of affiliation and conviviality devalued in the West can be affirmed in order to imagine a different economy of relation between adults and children, between the generations, between siblings, or between children themselves.

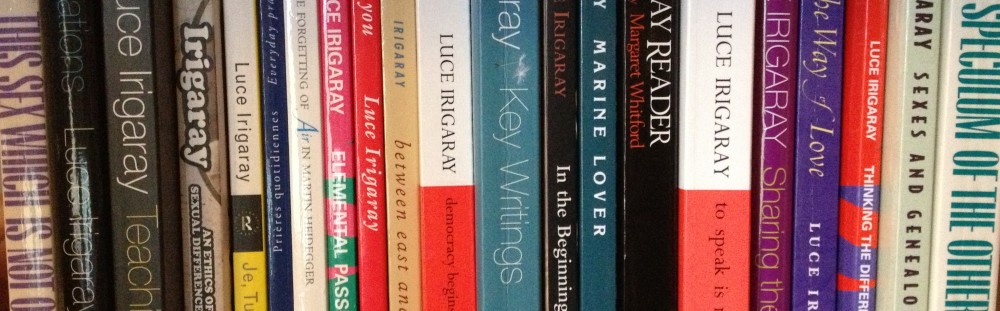

Luce Irigaray’s work offers a non-metaphysical framing of difference as sexuate, the only form of difference that is not conceptually reducible to the vertical lines of genealogy. (This is because sexuate difference is ontological, not merely cultural or sociological, as it is in many theories of gender. On this, see for example, Luce Irigaray, I Love to You: Sketch of a Possible Felicity in History, New York: Routledge, 1995, p. 35). For at the level of being there is no ‘child’ or ‘infant’ to speak of; both are metaphysical forms, not living beings and bodily morphologies. Now boys and girls are already sexuate identities, embodied forms determined by nature, though phallocentric modes of ostensibly natural education conceal this corporeality by opposing it to culture in order to render the child as a tabula rasa awaiting education by its adult others. Nevertheless, at birth, the girl-child and the boy-child receive an originary sexuation from their mother and father. It remains for Western culture to affirm and cultivate the sexuate difference of children from their parents instead of neutering it or abstracting it through metaphysical norms. This is not to say that children are restricted to the forms we presently term ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ but, instead they are induced to develop forms that they could take if their sexuate difference were affirmed are potentially infinite. At the present, though, there is only one form of subjectivity available, the masculine, and so any development of forms of embodied existence in childhood can proceed by way of the two instead of the one or the multiple (for example, Irigaray’s critical reading of the logic of the one and the multiple in Gilles Deleuze emerges poetically and in the infrastructure of Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. by Gillian C. Gill (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991).

If sexuate difference, which for Irigaray amalgamates the combines the ontic with the ontological, therefore carries within itself an immanent capacity for connection through difference, for the cultivation of the interval between the two, what modes might this cultured relation between adults and children begin to take?

Language, points out Irigaray, is a primary form of relationality in rethinking sexuate difference. In the case of children, the question might be: How can we listen to what children say? Not just in our adult language, our way of speaking, but in their own ways of speaking? How can we begin to enter into a dialogue by accepting that we do not know children finally, that we cannot know the world in which they already dwell, in which their becoming take forms, all things that we have for so long misrecognized or suppressed? How can adults share with children across the generations without reducing a girl or a boy to the neutral designation of ‘the child’? In what way can children, in turn, accede to their proper kinds of creative autonomy in relations that affirm sexuate difference? In what would this way of speaking consist? In the case of the institution of the school, for instance, how could an education in sexuate difference take shape? (see Luce Irigaray, ‘Towards a Sharing of Speech,’ in Key Writings, London: Continuum, 2004, pp. 77-97; and ‘Teaching How to Meet in Difference,’ in Luce Irigaray: Teaching, Luce Irigaray with Mary Green, eds., London: Bloomsbury, 2008, pp. 203-219).

The family, too, could evolve towards a different mode of relation if the sexuate difference of children were affirmed from birth. Rather than losing their difference in the body of the children, the mother and the father, or whatever two comprises the couple, could define one another through their irreducibility to their children and to one another. The relation between the mother and the girl-child or the boy-child, always already different from one another, does not already contain a ready made model for this relation, but instead offers an opportunity for creativity, for invention and novelty that would cultivate horizontal modes of relationality through difference. Not only relations of mother to boy, mother to girl, father to boy, or father to girl, but also sister to brother, aunt to nephew, or cousin to cousin (see for instance, Irigaray’s reflections on the brother-sister relation in In the Beginning She Was, London: Bloomsbury, 2012).

If the forms children take are affirmed in their difference, within an ethical project of cultivating a kind of ‘intersubjective dialectic’ between the generations, the potentiality inherent in the girls and boys whose childhoods populate our environment might provoke all sorts of becomings we have yet to even intuit, even in the most joyous affirmations of childishness, the tales children draw up to narrate their worlds, or the dreams and fantasy-lives to which they seem so much better inclined than adults (see for instance Luce Irigaray, I love to you, trans. Alison Martin, New York: Routledge, 1996; and ‘Pour une logique du intersubjectivite dans la différence’ in Das Leben Denken ,Tarbuck, 2007, pp. 325 -339). These creative experiments cannot take place, however, until the sexuate difference of children ceases to be negated so as to uphold the transformation of the child’s potential into a lesser version of the abstract, neutral adult subject.

Pingback: The Forms Children Take: Sexuate Difference and the Generations | Ecology and Reverie