My PhD is inspired by Luce Irigaray’s question posed in Sexes et Genealogies:

And where are we to find the imaginary and symbolic of life in the womb and the first corps-a-corps with the mother? In what darkness, what madness, do they lie abandoned? And the relationship to the placenta, that first home that surrounds us and whose aura accompanies our every step, how is that represented in our culture? No image has been formed for the placenta and hence we are constantly in danger of retreating into the original matrix, of seeking refuge in any open body, and forever nestling in the body of other women. (Sexes et Genealogies, p. 15)

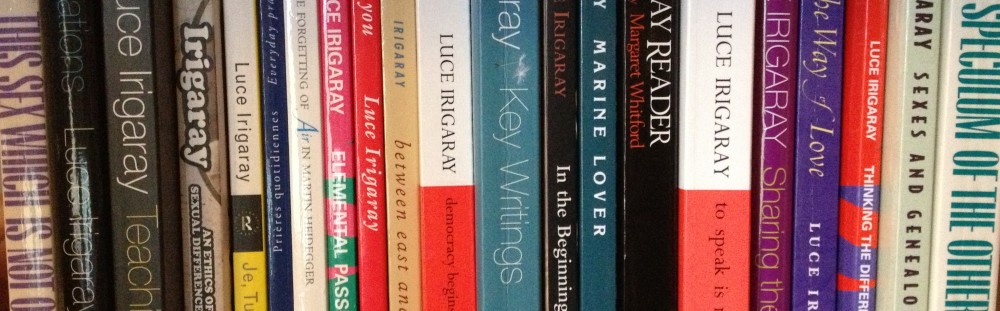

What does a consideration for the placental add to our understanding of ethical and philosophical perspectives on difference? I have worked as a birth doula beside women and their families during labour and birth for many years. My research is embedded within Irigaray’s writing and the sacred space of the woman-mother. Irigaray believes that we are always mothers just by being women and reminds us that we ‘bring many things into the world apart from children.’ (Sexes et Genealogies, p. 18). Irigaray critiques the predominantly masculine foundations of Western Philosophical thought, in particular its inability to acknowledge women as full subjects of the symbolic order. Instead of the binary logic subject-object, Irigaray puts forward a theory of sexuate difference between non- oppositional genders. She questions the denigration of aspects which correspond to what it means to be a woman. Irigaray proposes the notion of the woman-mother, the desiring woman and stresses the need to re-establish the mother-daughter genealogy.

What does a contemplation of the dialogue between the placenta and the mother’s body reveal? The placenta lives for 9 months and dies at the birth of the child. It is the only organ which behaves in this way. The afterbirth, as the placenta is known, is often assumed to be a part of the mother’s body, and, like the uncontrollable menstrual fluids, something which needs to be hidden and which one must dispose of as quickly as possible. The placenta is an organ formed by the embryo and has a half-mother, half-father genetic make-up. The foetus is consequently in part foreign in relation to the mother. After fertilisation, the placenta evolves as a halo enclosing the developing embryo, embedding itself in the uterine mucosa. The placenta is not confused with the foetus: it is connected, via an umbilical cord, to the navel. This implies that any cutting off the cord involves, as Lacan put it, a cutting off the foetus from a part of itself. The mother’s body recognizes the placenta as different, as other, and yet permits this foreign organ to develop inside the uterine walls. The presence of paternal genes within the embryo-placenta might activate the defense mechanisms of the mother’s body. Helene Rouche, a biologist, in an interview with Luce Irigaray, comments on the placental economy in Je, Tu, Nous (pp. 32-38). She notes how it is the placenta, in dialogue with the mother’s body, which prevents any rejection of the foetus. The placenta acts thus as a mediator in the relationship between the foetus and the maternal uterus.

Irigaray sees desire as driven by a longing to return to the place where we began, notably in the maternal body. We are not all born women so we cannot return to the mother in the same way. When we enter the symbolic order, we would learn who we are by discovering how our living bodies are related to and differentiated from the source of our desire for the maternal body. Lacan and Freud believe that a third figure is needed to resolve the mother-child intensely close relation, namely, the law of the father. The father ought to sever the link between the child and the mother. To remain tied-up with the maternal body is deemed taboo. Debra Bergoffen notes how Irigaray sees this banning of the mother’s body is a ‘recipe for violence and destruction’ (Bergoffen in Returning to Irigaray, Feminist Politics and the Question of Unity, p. 153). If we don’t find our body’s language, it will have too few gestures to accompany our story’ states Irigaray.(Irigaray cited in Reading Art, Reading Irigaray, p.102)

In ‘Belief Itself’ (Sexes and Genealogies, pp. 28-33), Irigaray comments on the Derrida’s discussion of the Fort-da defined by Freud starting from the gesture of the of little Ernst, Freud’s illustration of the way in which a little boy masters the absence of his mother. He would hold the reel attached to a string and throw it into and out of the curtained bed alternatively noticing that the reel was gone (fort) and then here (da). Irigaray hypothesises that ‘it could’nt have been a girl. Why? A girl does not make the same gestures when her mother goes away. She does not play with a string (un fil) and a reel symbolising her mother, because her mother is of the same sex as she is and cannot have the object status of a reel. The mother is of the same subjective identity as she is.’ (Sexes et Genealogies, p. 97) According to Irigaray, little girls do one of three things. She may throw herself down in distress, neither eating, nor speaking, completely anorexic. These symptoms of hysteria are a revolt against her loss. She might play with a doll which allows her to organise a symbolic space around herself. For the little girl, this gift space is a means of mediating her subjectivity to herself and to others. A third way in which girls cope with the absence of their mothers is through dance, in particular a whirling or spinning spiral gesture. The dance is also a way for her to create a territory of her own in relation to the mother.

My PhD will excavate and articulate the ancient language of which Irigaray writes, ‘the relationship to our mother’s body, to our body.’ Within the intra-uterine space, a relation between two different and irreducible subjects is made possible by the mediating presence of the placenta.