My journey has started with my own and my mother experiences of living through, learning from and surviving domestic violence in my family over a 23 years period. As the eldest daughter, who not only has a close relationship with my mother but was also a witness to the domestic violence, I absorbed all the emotions she was undergoing. I put myself ‘in her shoes’, trying to figure out what I would do if I were in her situation. Divorcing definitely would be only my answer. And I was very disappointed by and disagreed with her “choice” to stay.

Despite our loving each other very much, there is a black hole between us that we never approached nor understood. As Irigaray explained (Why different? p. 30) “They remain strangers, they are accomplices on some level, blind to each other on another”. Faced with an agonizing dilemma in a close relationship with my mother, as a daughter in a domestic violence, according to Irigaray, “I see the mother-daughter relationship as the dark continent. The darkest point of our social order (…) this suffering is expressed through tears and screams. I translated into a ‘silence’ between mother and daughter” (op.cit., p. 18).

I started with having a bad and antagonistic reactions against my mother; I hated her womanliness, weakness and powerless surrendering to her family.

The more I reacted against my father in many ways, the more my mother was saddened and distressed. I was increasingly confused and upset by her responses. I believed I was helping her, but instead she encouraged me to try to understand my father, which I could not accept.

The domestic violence in my family ended in my misleadingly seeing how my father was more powerful than my mother, which effected me and my sense of identity. I hated my womanliness that placed me in a passive and powerless position as that of my mother.

After recognizing my critical perspective in applying a “feminist lens” and “auto-ethnographic” methodology, I was inspired to think more radically and work differently regarding domestic violence. This has opened a broader horizon in which I could approach my mother as a “subject”. I also approached my father, an abuser, through a gender lens rather than from the perspective of a mental disorder or the condition of an individual suffering from psychosis. Moreover, I approached myself through a reflexive process, which allowed me to deal actively with the domestic violence and freed me from pain and hate.

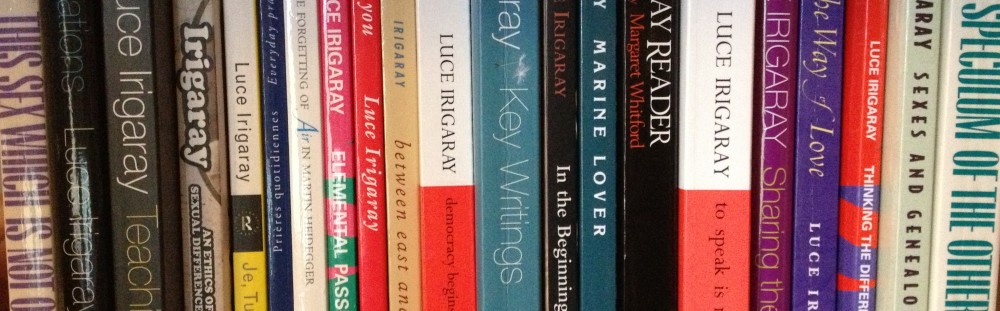

I profoundly learned and understood by reading Luce Irigaray’s text ‘Approaching the Other as Other ’ (Key Writings, 2004, pp. 23-27). When I imposed my thought and expectation on my mother, I inadvertently neglected her own conviction, subjectivity, individuality and humanity. I ignored her right to have personal feelings, that is, her love, hate, passion and desire, to the extent that I expected her to disregard her own being. As I realized that she has a subjectivity of her own, I came to understand and have more respect for my mother, her thoughts and decisions. Finally, I became proud of being a woman, a daughter and came to love and respect my mother and myself more.

In 2011, my personal experience as a mother of a 6 years old boy, led me to take interest in another academic area, that of motherhood. With severe tiredness, bad-tempered confusion, I eventually developed so that I could address the various and inexplicable states of motherhood. Notably, I realized that being a mother is an exceptional experience, I discovered my subjectivity, my self-affection, and a deeper way of loving. This grew from a certain detachment which inspired me to experience freedom in love – which liberated me from love as possessiveness, and instead led me to take a primal step toward the love of a human being. As Irigaray mentioned in Democracy Begins Between Two (p. 9), “If we take respect for the individual as such, with his/her qualities and differences, as our starting point, it is possible to define a form of citizenship appropriates to the necessities of our age: coexistence of the sexes, of generations, races and traditions”.

To experience what my mother was living while being myself a mother has crystallized in me the realization that a mother’s journey can enlighten us on how to perceive and respect the bonds of love and an intimate relationship with our surrounding as a way of reaching the secular enlightenment which maintains our humanity and community.

Women’s Enlightenment : Way of Engaging

The enlightenment way towards the Buddhism enlightenment (Dheravat) in Thailand is remarkable for which it requires one to practice meditation in a retreat; that is, by living in isolation and seclusion from distractions, relationships and intimate relationships. However, only men can be monks, given that Buddhism is currently practiced under masculine authority.

The traditional process of transition to become a “man” is covered by the sacred grand narrative, which is upheld by a yellow robe, a monk’s uniform that will ensure parents to reach Nirvana in the next life. Therefore, it is a symbol to enshrine men’s privilege for “only men” can reach or lead parents to Nirvana. Meanwhile, women will never reach or bring parents close to Nirvana in this religious tradition.

The enlightenment state in Buddhism clearly emerge by seclusion and meditative practices. I thus wonder how it would be practically difficult to reach it for a woman and mother who mostly take responsibilities, as nurturers and caregivers for children, family, parents and community. As women we have to think about ourselves and others all the times, and we cannot leave everything and everyone in order to undertake the journey of a religious enlightenment, alone for such a long term. But we can find a way to enlighten ourselves together on the path of a spiritual growth through relationships as those which I have experienced from my mother and other mothers towards becoming a woman and mother. Indeed, we always and forever learn how to practice the respect for ourselves and for the other(s) in our everyday’s life and relationships, notably by forgiving, understanding and ultimately respecting our partners, our children, our families, which extensively contributes to supporting our community (Democracy Begins Between Two, 2001).