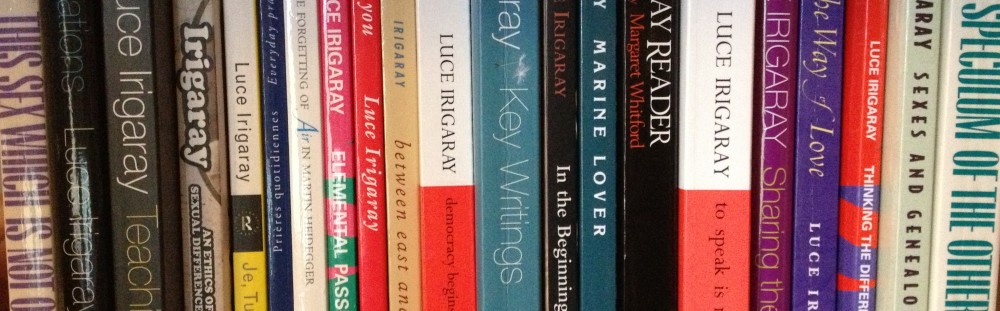

My PhD project investigates the concept of justice as it appears in the work of Luce Irigaray. It attempts to think-through this concept with reference to the crime of rape. The failure of law as a tool deft enough to adequately respond to the complexity of sexual violence is a criticism long made by feminist writers. In England and Wales, the Sexual Offences Act 2003 instigated major reform of both the actus reus and mens rea components of rape with virtually no corresponding increase in conviction rates. Despite the many failings of the criminal justice system a significant number of women continue to call at the door of the law in search of justice in the aftermath of rape. As is clear listening to the narratives of victims of rape, the law continues to provides an important framework of reference against which many women measure and judge their experience of violation and indeed seek redress or ‘justice’.

For this reason, I contend that feminism should not turn its back on the criminal justice system but that it should continue asking questions of the law, albeit, I argue, with a more creative and critical focus. To this end, and drawing together themes from Irigaray’s work, it seeks to address following the question: what should women who are raped be entitled to aspire to in the name of justice?

A vision of justice that emerges from an analysis of Irigaray’s oeuvre is one that combines notions of civic personhood and individuality with mutuality and community. It is one that makes a commitment to normative principles like dignity and self-respect and that valorises an individual’s right to ‘become’ in accordance with one’s unique (sexual) difference. It is also one which bases its political commitments upon utopian ideals and engages the law in seeking to honour these commitments.

Irigaray’s conception of sexual difference provides a practical ethics through which it is possible to think a civic existence for women in accordance with their own genealogy and outside the simple inversion of power relations that formal equality promotes. Considering sexual difference in this way, and concurrently with the theme of the right to ‘become’, generates potentially unthought-of possibilities for what a rape complainant should then be entitled to as justice in the aftermath of rape.

If a just civic existence involves the entitlement to ‘become’ in accordance with one’s own unique sexual identity the wrong of rape is thus an interruption, an assault on or a retardation of this process of becoming. One account of justice from this view point might then involve the guarantee of resources (one of which might be the trial) in order to facilitate the continuation of that process of becoming. A reconceptualised notion of justice informed by these considerations might even reposition or displace the trial from the privileged monopoly it holds on dispensing law and ‘justice’. This would involve a revaluation of what we consider as ‘just’ as not necessarily defined or understood as beginning or ending at the trial but as involving the whole entry into and participation in social life.

This repositioning of the trial as only part of a possible coordinated response to the crime of rape necessarily implicates a movement away from commanding concepts valorised by the trial like procedure and legality. The alternative vision of justice that I have extracted from Irigaray’s work leans towards an emphasis on dignity and identity as central to a governing ethics of sexual difference. This change in focus might not necessarily demand new procedure but might engender a new way of ‘being together’ in a trial setting, for example, and addressing the harm of rape. It might also reposition the official focus of the resolution of such a crime away from traditional paradigms of punishment solely aimed at the body of the offender towards the restoration or ontological repair of the victim.

Finally, Irigaray’s utopian imagining of a civic existence of two has the potential to generate a justice for rape complainants not bound by the strictures of the current juridical system. Applying such thinking to the rape trial could generate, for example, the construction of a utopian model of adjudication which seeks to create a microcosm of social and political justice within its trial space, thus engaging an ethics of sexual difference. This model might involve the use, legitimation and nurturing of different narrative traditions and the abandonment of a particular discursive hierarchy which frequently alienates complainants of rape during the trial. This then would require the acknowledgment and respect for asymmetric interpersonal relations, or for ‘difference’, within the trial space and the possible deconstruction of concepts like neutrality and impartiality upon which the fiction of legal justice is currently based. Simply providing a space for such an imaginary then also encourages the rape complainant to think through her injury and her own unique needs beyond the limits of what the legal system prescribes as adequate.

A victim of rape experiences a unique personal harm that cannot be generalised but the spectre of which haunts all women. The failure of law reform in this area demands that feminists consider a new approach to the crime of rape. This project is an attempt to initiate that discussion by rethinking what we understand as a just response to rape, constrained not by the limits of a legal system that has been shown to be complicit in the maintenance of a rape culture, but guided by the heterogeniety of women’s experience and by an alternative vision of justice thought through the work of Luce Irigaray.