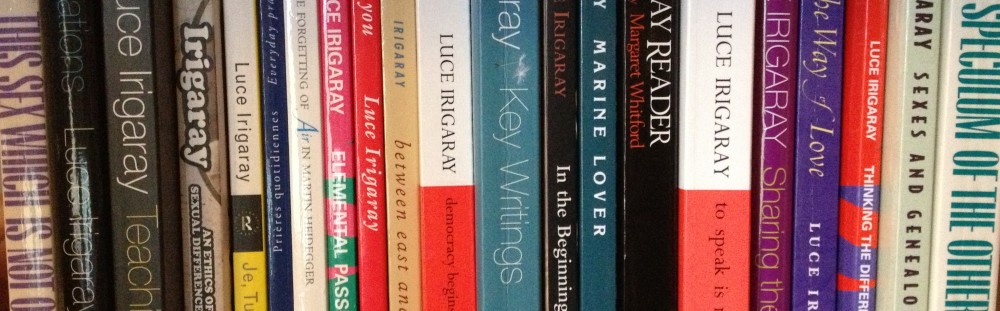

Irigaray’s reading of Plato’s cave in Speculum patiently unpacks the disavowal of maternal beginnings in the inaugurating scene of Western political philosophy. If the phallic structure of psychic identity formation depends on a radical severance from maternal attachments leading to a masculine appropriation of the feminine and its erasure as such, Irigaray shows that this phallic cut goes on in all the conceptual work and is of use for founding truth in Plato’s thinking. She carefully maps the elements of the cave onto feminine anatomy (mapping the entrance, little wall, and internal space of the cave as vagina, hymen, and uterus), interpreting Plato’s metaphorical conception of Truth as light to be premised upon the displacement of the feminine-maternal. The relation to the maternal beginnings is disavowed and is replaced by another origin story, one that is signified by the space of darkness, illusions, and servitude. In this scenography, the task of birthing, of conception is now originally assumed by the (male) philosopher, who knows himself as the only one able to deliver men (“sex unspecified”) from the chains of falsehood into the world of light and the progressive movement towards the Truth of eternal forms.

My reading of Irigaray focuses on two main interventions. The first is the one of the intervention of phallic time in the epistemic becoming of man. Imagining the feminine as the negation of light and birth, that is, as the darkness and death-like static condition of the womb/cave, is depending on the relegation of the feminine to a place outside of time. The situation of the cave is frozen and still. There are no movements and no changes inside. Time is arrested. However, in man’s narrative the forward, unidirectional and rectilinear evolution of time organizes the scene both inside and outside the cave. Inside, the men have their gazes fixed forward with their backs towards the origin. And the allegory is set to move the men straight out and above the cave towards the light of the sun. Irigaray’s reading shows that the presumeddead time of the feminine re-emerges in the gaps and slits that open up in the forward movement of man, particularly in surges of the memories of the cave that for Plato could be left behind, again and again, through necessary times for adjustment to the light. Feminine time, therefore, already bears within it a kind of melancholic mourning, not a radical severance from maternal beginnings but a remaining in touch with a past that breaks the present open and puts into question a projected future.

My second interest in this essay focuses on the question about why an orientation towards sensitivity is associated with confinement and slavery in Plato’s work. Irigaray’s reading suggests that the operating principle of this scenography the principle of identity. The men inside the cave are identical to one another, all occupying the same position, having the same gaze, and arriving at the same conclusions. They are also “like us”, because we too are captivated by illusions without the intervention of philosophy. Therefore, the representation of life inside the cave is the same as that of life outside the cave, wherein shadows and falsehoods are reproduced. Then perhaps the chains holding men in bondage must not necessarily be associated with sensitivity as a cause of darkness, but rather to the principle of sameness itself. Anidentity determined by sameness binds us to each other without the possibility of differing from each other, and the Being that is to be achieved from a progressive philosophical evolution is destined to remain under the control of the sameness even in the domain of the intelligible. The opening force of sexuate difference within the human being has to do with the time of woman who seeks anther modality of assumption of the maternal loss. Instead of a radical erasure and appropriation of maternal beginnings, which require an endless repetition of an initial violence to sustain its projective motion, the path that can break the violence resulting from this kind of identity is a semi-grieving relation and not a radical disavowal.

In another instance of such a denial and forgetting of the maternal-feminine, I take up Irigaray’s reading of Nietzsche in the section of The Marine Lover called “Mourning in Labyrinths.” My interest here is how another conception of time, the Nietzschean “eternal return of the same,” which intends to oppose the Platonic direction towards the essence of the Idea, is still founded, on the one hand, from/on the erasure of woman, and on the other hand, stuck, not in a fixed identity of being, but in the solipsistic labyrinth of becoming. At the heart of all that, ways of loss are at stake.

Irigaray’s passages are layered, interwoven, and dense, and I can retrace only a few of their main steps. The first is that the eternal return is premised on the murder of God. It is this death that opens the horizon of the becoming God of man, and thus the possibility of a will that can will some eternal possibility. From the outset, we are in the milieu of a disavowed grief, a melancholic incorporation of God. But this grief has a forgotten history. Irigaray alludes to both a future and a past confusion of God with the other as woman. The murder of God is symptomatic of a desire for the murder of maternal beginnings, the latter having been substituted by an origin story related to God. It is thus a repetition of an originally repressed murder of woman, one that is now bound to a return against the new subject of origins, man himself. But it is also the murder of the other as present or to-come, foreclosing the possibility of a relation with an external difference. About this closure, Irigaray analyses what she calls Nietzsche’s “greatest ressentiment” which would havebeen arisen from woman. She plays on a distinction between two Nietzsche’s songs, “Ariadne’s Lament” and “Fame and Eternity,” that is, between two feminine figures, Ariadne and Eternity. The former concerns woman and an ambiguous mourning for her lover Dionysus, at once rejecting and desiring him. She is trapped in a labyrinthine love of Dionysus. The latter, Eternity, represents a yes expressing the mute beauty whom Nietzsche desires. According to me, Irigaray’s crucial interpretation is that Nietzsche’s ressentiment is a reaction to woman’s ‘no’, a ‘no’ that is not total and absolute like the divine ‘Thou Shalt Not’, but nonetheless interrupts the temporality corresponding to an eternal retour of the same. Eternity’s ‘yes’ supports the process of Nietzsche’s becoming, but the substitution of woman for it aborts thedevelopment of his desire. Without a desire for the other, he too is entrapped in a labyrinth, the one of his own becoming. This maze can be a form of mourning for the other, but it relates neither to its own source nor to its path away.

Irigaray’s call for the recognition of difference assumes the process of a temporality that folds into inaccessible depths. “Let it be a return to something that has never taken place,” she writes. I read that as the structure of a kind ofmourning at the root of the feminine desire, as a relation to loss that allows a return without repetition and without frozenidentity, in faithfulness to that which had not, or not yet, revealed itself.