My research addresses the question about how women have been viewed in the workplace, the home, and society through the historical lens of philosophy. I take a very critical stance to consider not only the role of women but even if one can begin to justify the presence of the other in this convoluted, multidimensional, and changing world. In this world, we are invited to share space. We must carry this non-imposed and ethical responsibility to experience the sharing of an identifiable and respectful space. But what does that mean? Are we sharing space or diminishing this space by filling it with our personal insecurities and irrational demands that linger on material satiations? Irigaray and many other thinkers such as Kant, Leibniz, and Newton have attempted to define the cost associated with the ambiguous concept of space and time for those who strive to share space equally and generously. In his Critique Of Pure Reason, Kant implores the readers to think of space as corresponding either to a subjective constitution of our mind or to a form of intuition. He also claims that space and time can never be shared equally between two individuals because they never can have the same intention. For the modernist people, time is at the root of sharing deadlines and completing projects. But at Kant’s time it means an intuitive concept which, when overtaken by space, becomes indispensable to define the methods adopted whenone intends to share space because the motive for sharing space is always changing. This raises a problem because one subjectivity attempts to occupy most space that it is possible. Furthermore, each subjectivity results from a sense of self, occupations, but also relationship with the other.

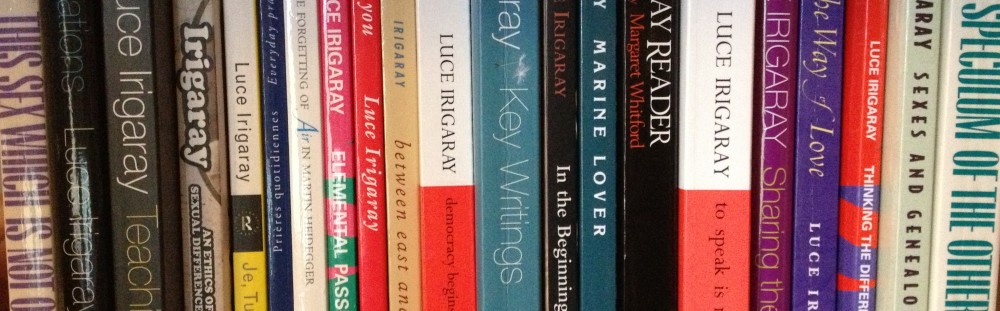

My focus depends on the work of Luce Irigaray, for whom the self is an a priori fundamental notion. According to Irigaray’s view, a self-identified woman may experience herself as both a subject and an object. She may also desire “carnal love” when she is torn between two objectives (Irigaray, To Be Two, 28), but this is suppressed because of societal implications. For me, Irigaray’s work is most precise when it refers to women’s subjectivities through which a portrayal of sharing space with the other can be contextualized. Irigaray does that by treating the topic of womanhood and articulating a feminine discourse. In her work, she shows that despite women maintaining a consistent subjectivity in our society, they are denied many aspects of agency and independence. She questions classic views on the significance of the difference between feminine and masculine representations of sex organs, and the experience of erotic pleasure by gendered subjects.

Additionally, Irigaray discusses how the masculine subject has an advantage over the feminine subject when experiencing erotic, bodily pleasures. The feminine subject offers “an opening” to the male’s sex. But where, in a masculine subject, lies space for expression of women’s erotic feelings? This must be felt, carved, and ultimately claimed by the feminine subject. Claiming space for both bodily and intellectual expression is an indispensable phenomenological concern for Irigaray because it allows the formation and an accurate suitable representation towards a new identity. In An Ethics of Sexual Difference, Irigaray approaches and reports a longstanding philosophical problem concerning the dichotomy of genders in philosophy, sciences, and psychoanalysis. Similarly, in Speculum, she strongly responds to her counterparts, by pioneering feminist theory which is crucial to understand the woman’s body, mind, and intersubjective relationality at an epistemological level. She has explored characteristics that a woman might possess through psychological, physical, and mental experience in virtue of her place in the culture that she inhabits.

In my paper, I also compare Levinas’ phenomenology concerning the other with Irigaray’s thinking about sexuatedifference. Irigaray’s work describes the relationship between two sexuately different subjects as taking account of the global being of each subject, as well as of a radical respect for the alterity and transcendence of the other. To reach the possibility of a contact with an other who is sexuately different, what Irigaray calls hetero-affection, each subject must be capable of opening to the other and letting this subject be. Each subject must also be capable of retaining his or heridentity and returning to him or herself thanks to self-affection. This twofold structure of hetero and self-affection has to do with Levinas’ goal to resist the privilege of the same and to gain an ontological solitude.

Levinas’ distinction of the roles between woman in the home as the guardian of the family unit and man as citizen transcending a mere natural being is mistaken given his way of conceiving of the difference between the two sexes. Irigaray claims that the reduction of woman to such a function can be avoided by considering her responsibility first for her self and, then, for the other. According to Irigaray, self-responsibility is needed to meet the other; therefore, my acknowledgment of the other as other is dependend on my responsibility for myself.

Besides, this dichotomy reveals several ethical concerns of Levinas’ theory concerning the preservation of an ethical and just relationship. The woman is not really recognized for her labor in the home, and this prevents her possible possession of the home and implies that she can never assume the role of an owner, a master, and even of a subject of love.If the home, labor, and possession are concrete actualizations of our being for Levinas, in this case, they accomplish in an ontological significant manner the work of “the separated being effectuating its separation”. As such, they incarnate a spontaneous ontology, an ontology before all formalized ontologies. In fact, Levinas has overlooked a relation capable of overcoming the world of the “I” and the egoistic “I am.” That is why Irigaray’s ethics of sexual, and more generally sexuate, difference completes Levinas’ thinking about human responsibility for the other, especially for the feminine other, because it both upholds the difference between man and woman as gendered, and it preserves Levinas’consideration for the same. This way of thinking of the feminine is most suitable to envisage Levinas’ social ontology of the home because it takes into consideration (a) self-responsibility and the woman as able to actualize herself as anembodied subject of love, labor, and possession; (b) responsibility for the other by first fulfilling responsibility for oneself. So the woman avoids becoming a masculine means of achieving alterity and, instead, ensures an indispensable condition to sustain life in the home and beyond.