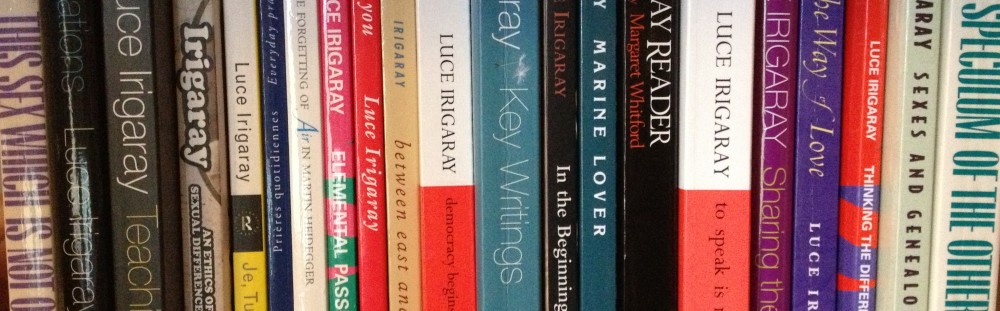

The work of Luce Irigaray has been fundamental for my dissertation, in which I study representations of mother-daughter relationships in novels and memoirs by Colombian and Colombian American women writers. My presentation for the seminar was an analysis of a memoir by Daisy Hernández (1975), an American writer and journalist of Colombian and Cuban descent, in light of Irigaray’s conception of self-affection as necessary for women’s individuation – particularly to overcome immediacy in relationship with their mother and reach their own identity as sexuate subjects.

A Cup of Water Under My Bed (2014), is a coming-of-age story of Daisy’s life growing up in New Jersey with her strong Colombian mother and aunts, and her Cuban father. Her memoir has been highly praised for her skillful treatment of issues of gender, race, class, sexuality, immigration and family relationships. As a feminist and woman of color, Daisy Hernández highlights in her memoir the mother-daughter relationship and the relationship among other women in her family in order to situate herself within a “female genealogy so that [she] can win and hold on to [her] identity” (Irigaray, Sexes and Genealogies, p. 19). Consequently, I argue that through her “life-writing,” Daisy Hernández constructs her identity as a journey that involves a departure from and a return to home. This process encompasses her own growth towards self-loving and building a home thanks to self-affection – which is defined by Irigaray as “a relation of intimacy with ourselves that allows us to stay in ourselves when relating with the other, an ability to remain in oneself as in a home” (‘Toward a Mutual Hospitality’, in The Conditions of Hospitality: Ethics, Politics, and Aesthetics on the Threshold of the Possible, p.52). As explained by Irigaray during the seminar, this process is not easy, but it is absolutely necessary to cultivate relationships in difference.

From the beginning of her memoir, Daisy places emphasis on the mother-daughter relationship. She dedicates her book “para todas las hijas” [for all the daughters] and this dedication is followed by a quote from the renowned Chicana writer Sandra Cisneros: “What does a woman inherit that tells her how to go?” The memoir is divided into three sections with a total of twelve chapters. The first section deals with language, her mother’s genealogy, and religion; the second focuses on Daisy’s reflections on gender and sexuality and her family’s reactions to her bisexuality; and the last section concentrates on her father, economic issues, and her working world.

I read Daisy’s memoir as a way of paying homage to the women in her family, who struggled in different manners for gaining their independence. Leaving their home and their mother in Colombia was a painful process for them and an experience that Daisy also met with difficulty. Irigaray maintains that “one of the lost crossroads of our becoming women lies in the blurring and erasure of our relationships to our mothers and in our obligation to submit to the laws of the world of men-amongst-themselves” (Thinking the Difference: For a Peaceful Revolution, p. 99). Thus, a separation between mother and daughter in order to submit to the world of men-amongst-themselves is an experience that, for these women, hinders the process for learning to love themselves as women. As Irigaray illustrates with examples from Greek Mythology – notably the story of the separation between Demeter and her daughter Persephone and their subsequent happy reunion – “any woman today who is trying to find the traces of her estrangement from her mother” has to “go back in time” (op.cit., p. 107). Irigaray likens this reliving and telling one’s experiences to a psychoanalytical cure. While I cannot affirm that this is what Daisy does with her narrative, she does say that “writing is how I leave my family and how I take them with me” (p. 179). As I have stated before, placing herself in her maternal genealogy allows Daisy to strengthen the bond with the women of her family as her identity formation process advances, especially because, as Irigaray insists, “innerness, self-intimacy, for a woman, can be established or re-established only through the mother-daughter, daughter-mother relationship which woman re-plays for herself. Herself with herself, in advance of any procreation” (An Ethics of Sexual Difference, p. 68).

The protagonist of the memoir A Cup of Water Under My Bed challenges the traditional expectations of her Latino family and takes control of her life. Although Daisy was born in the United States, she has to overcome obstacles posed by the different aspects of her identity. Daisy not only has to overcome hindrances in becoming educated, but also in finding love and being accepted by her family. Her (bi)sexuality causes friction with the women of her family, along with her adoption of feminism. In her quest for achieving a coherent identity, Daisy has to come to terms with language(s), class, religion, sexuality, family values, ethnicity and political views. She leaves home to return later to her own ‘home’, a place within herself that allows her to gain and preserve her identity while relating to others – as it can happen in a state of “self-affection” which , according to Irigaray: “ ought to evoke a state of gathering with oneself and of meditative quietness without concentration on a precise theme” (‘Toward a Mutual Hospitality.’, in op.cit., p.52). Through meditating on how the axes of her identity intersect, Daisy’s memoir explores contemporary representations of LatinXwomen of colour, and how they have to deal with the different and often conflicting dimensions of their identities.

By giving a central place in her memoir to female genealogy, Hernández’s story puts into practice Irigaray’s recommendation: “How are we to give girls the possibility of spirit or soul? We can do it through subjective relations between mothers and daughters” (je, tu, nous: Toward a Culture of Difference, p. 47). Even though, at times, Daisy feels misunderstood by her mother and aunts, she nonetheless values their experiences and tries to “establish a woman-to-woman relationship of reciprocity with [them]” regardless of their different convictions and ideologies (cf. ‘Women-Mother, the Silent Substratum of the Social Order’ in The Irigaray Reader, by Margareth Whitford, p. 50). As exemplified by this 2014 memoir, fiction and non-fiction by Latina writers continue to portray genealogies of women. Thus, the work of Luce Irigaray is of use to illuminate the relevance of these genealogies to form better alliances between women, and also between men and women, in our present times.