Allegiances to God or gods aside, and inheritances of religious history and ritual suspended momentarily, we return with Irigaray „to the most simple of everyday life”, where simple things are „always relational – whether it is a matter of the relation to nature, to things, to the other” (Luce Irigaray, „Beyond Totem and Idol, the Sexuate Other”, Continental Philosophy Review 40, no. 4 (2007), pp. 356-7). In pursuit of our spiritual becoming, we meet in a common place, a domestic space where our humanity is most unmistakable.

The experience of the Luce Irigaray Seminar was not unlike this. The rhythm of meeting, listening, speaking, keeping silence and sharing hospitality together enabled a kind of learning (of self, other and the work of philosophy) that typical education experiences don’t. Luce Irigaray facilitated a learning space that was relational and in keeping with the logic of her own ethical project. This process was both validating and challenging: acknowledging each other with respect to difference; and testing boundaries and limits of language, and culture as we know it.

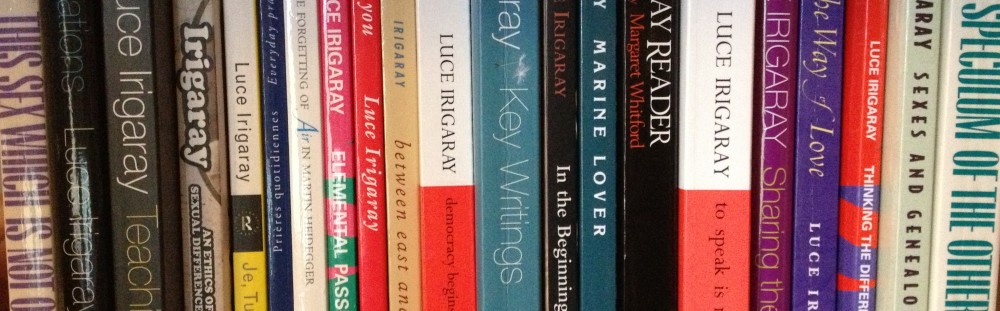

The work of Luce Irigaray, particularly her writing on spiritual becoming, has been influential in my own art practice and related PhD research, both currently focused on images of the body, specifically that of the mother. In her can be seen not only the physicality of biology, but also a spiritual propensity for hospitality and ultimately love in relation to an other. The mother’s body in action works as a symbol of liminality: an edge between distinction and inseparability from the other to whom she gives birth. The postural patterns her body makes towards her child indicate their original sharing of life and breath and also the state of spiritual relation between them. She is shown to be human and divine – her body demonstrating love, immanent and transcendent, at once touching and exceeding our reason and understanding. The body of the mother in this way figures Irigaray’s „sensible transcendental”: the body and its postures towards the other are a felt and generative gift, genealogically infinite, at once present and absent (Luce Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999, p. 94).

A return to this kind of imagery – however realistic or symbolic in its material form – offers us a way into the self and our origins in an other. In „Beyond totem and idol, the sexuate other”, Irigaray argues that our masculine Western culture forgets „this maternal mystery of the sharing of life and of breathing” (Luce Irigaray, „Beyond Totem and Idol, the Sexuate Other”…, p. 357). Failure to remember this first experience of internal acceptance has led to man’s tendency to perpetually separate from and maintain an external relation with the feminine other. We know historically and in our own time that this has been characterized by behaviours of dominance but also, as Irigaray identifies, by a taboo on spirituality.

The spirituality so demonstrably embodied by woman and her maternal potential challenges the Western patriarchal legacy of separating spirit and body and relegating them to man and woman respectively. According to Irigaray, this legacy fails to comprehend our whole humanity and so stifles our spiritual becoming. What is needed, she argues, is recognition of sexuate difference – of woman and man as real human subjects, different from each other and embodying different spiritual qualities. Just as God, a Wholly Other, is (philosophically and theologically) vertically transcendent to us, so the human other must be understood to be horizontally transcendent (Ibidem). In „Beyond totem and idol”, Irigaray argues further that our cultivation of sexuate energy (coming from difference rather than simply the act of sex itself) need be a primary task in our journey of spiritual becoming. Without it, we risk making idols of each other – cast as sacred and superior (thus demanding some kind of worship response) or entirely imperfect and forbidden (thus requiring utter denial and rejection).

For an art practice concerned with images of divine love, the long iconoclastic histories of religion loom cautionary, and urge a new approach that values difference and identifies patterns in our human experience and expressions of love. In pursuit of spiritual becoming, people have long generated objects – whether in replica or symbolic form, material or mental composition – to signify heightened moments of revelation and thought, or even ‘the Divine’ itself. The problem (not new in the age-old contestations of religious art) occurs when such representations become totems or idols, effectively locking up the divinity they mean to represent. Such fixed images can halt our spiritual development and close us off to the difference and transcendence of the (O)ther.

Irigaray encourages us to look again at the life of Jesus Christ as a story of great significance to our Western conceptions of human becoming and subsequent sharing of the world. Christ is posited as one who mysteriously connects two disparate cultures (totemic and patriarchal) (Ibidem, p. 362) and demonstrates „the absolute necessity of love in a human becoming, in a divine becoming” (Luce Irigaray, Key Writings, London: Continuum, 2004, p. 150)

Irigaray continues with a personal account of her (re)turn to the tradition, upon which the reality of her feminine subjectivity radically opens up a new relation with the person of Jesus and subsequently reformulates a theological understanding of the incarnation:

„This revelation of a Jesus whose incarnation is the path for a more fulfilled human becoming speaks to me, invites me to progress towards a more accomplished feminine identity. First of all, this means not considering myself as purely body, with only a natural capacity for engendering children, more or less spiritual, depending on whether the seed of the father is this or that. Putting myself in search of my word, my words, seems to be the first fidelity to a theology of incarnation” (Ibidem, p. 151).

Luce Irigaray proposes in Key Writings, that „to reach, with vigilance and responsibility, a theology of incarnation and love requires us first therefore to discover our spiritual path as women (Ibidem, p. 152). And so I am challenged with her to cultivate my words, my own feminine subjectivity,characterised by „interweaving relations with other subjects” and language that communicates with rather than conquers or appropriates the other. And beyond words, to create my art, with the hope of opening up fresh and collaborative ways of conceiving of revelation, truth and sacredness relevant to life shared today, both inside the cathedral and beyond its walls.

Bibliography

Irigaray, Luce. “Beyond Totem and Idol, the Sexuate Other.” Continental Philosophy Review 40, no. 4 (12/07/ 2007): 353-64.

——. The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999.

——. Luce Irigaray: Key Writings. London: Continuum, 2004.