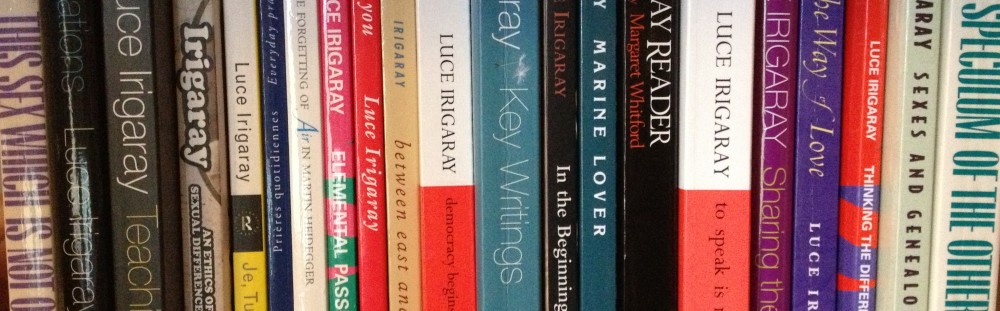

The girl is a critical point for the revolution of culture, according to Luce Irigaray. As such, we can productively trace Irigaray’s engagement with the girl over several decades through her philosophy. This ranges from her important critiques of the Freudian little girl in Speculum of the Other Woman, to later considerations of Antigone, Persephone/Kore and the little girl’s dialogue with the mother. These texts take up and question the discourses of myth, linguistics, psychoanalysis and philosophy with clear attention to the girl but also through an engagement which is framed by her primary philosophical concern — the question of sexuate difference.

In film studies and film philosophy there has been a recent shift that engages with Luce Irigaray’s philosophies of sexual difference in relation to narrative cinema. Whilst feminist film theorists such as Mary Anne Doane, Annette Kuhn, Teresa de Lauretis and Kaja Silverman have long drawn on Irigaray’s theories to make important interventions in feminist theories of spectatorship and cinema in the 1980s and 1990s, more recent interventions take up Irigaray’s theories as a philosophy for narrative cinema. Here film scholars such as Caroline Bainbridge, Lucy Bolton, Liz Watkins and Davina Quinlivan explicitly set out to engage the politics of Irigarayan philosophy with film, offering a certain perspective on film and the viewer.

Through the philosophical project of Irigaray we find a unique critical problematisation of ethical relations, sexuate difference and feminine desire that I argue is necessary to engage with to theoretically ground and open up an exploration of specific audio-visual art practices. My research thinks seriously about sexuate difference with the audio-visual and does this through attention to the girl. Within this project it seeks also to explore how the girl might be a pivotal and vital figure for feminist thought more broadly. For, despite the girl being relegated to the margins in mainstream feminist discourse and scholarship on the moving image, I argue she is a productive figure with whom we must think with if we take the problematics of feminism and sexual difference seriously.

Through the girl, and especially her words expressed to others, we can approach an intersubjective relationship that respects sexuate difference, as Irigaray understands it. The girl is doubly interesting for me in Irigaray’s thought because not only does she offer a way toward creating a new culture which respects being in two, but conversely the girl is one with the most potential for dereliction in phallocentric culture as it stands because, following Irigaray, mediation is foreign to them. The girl, therefore, has the most at stake in the questions Irigaray poses and is a vital figure to attend to.

In Sexes and Genealogies Irigaray argues that girls do not enter language in the same way as boys. Her analysis shows how the girl is in a different relational context. Thinking about Freud’s articulation of the child’s coming into language in his theory of Fort/da she argues that the theory does not give enough attention to gesture and sound together. She also suggests that there is a different ensemble of sounds, gestures and actions specific to the little girl. The little girl has a different relational context than the little boy to the mother and a different way of coming into language. She writes:

[T]hey enter language by producing a space, a path, a river, a dance, a rhythm, a song… Girls describe a space around themselves rather than displacing a substitute object from one place into another or into various places. (Irigaray, Sexes and Genealogies New York, Columbia University Press, 1993 p.97)

Irigaray describes, by foregrounding a sense of movement in space, the specific gestures of the girl produced in relation to the experience of the absence of the mother. In this moment the girl does not displace a substitute object, as we see in the case of Freud’s little Hans, but produces or describes a space around herself. Irigaray continues:

[Girls] interiorize the greatest distances without dichotomic alternations, except that they whirl about in different directions: toward the outside, toward the inside, on the border between the two. (Luce Irigaray, Sexes and Genealogies New York, Columbia University Press, 1993, p.99.)

The specificity of the girl’s movements relates to the ways in which she engages with others through language and culture without taking an object. She opens up a space where she can be herself but also open to another. What Irigaray tells us in this essay, is not only do girls enter language in a different way to boys, but to read such difference simply through sound and orality renders this specificity as mere lack and silence. These specific gestures and sounds express what Irigaray calls a ‘different axis of relations’ of the girl to her self but also to others. If this axis cannot be fostered or sustained in our culture then she is forced to engage in a model of being that tries to master the object, rather than be with another subject.

The question of subject-subject relations, rather than subject-object relations, is addressed by Irigaray again in her later book I Love To You using her training in linguistics to think about the possibility of an ethical relation that respects sexuate difference. The girl is important in this book because she is a figure who approaches a dialogue which might respect two subjects in their difference. Irigaray writes:

Little girls speak lovingly and socially, adolescent girls dream of sharing love. Little girls and adolescent girls reveal a desire for intersubjective relations: of life with. (Luce Irigaray, I Love To You, London and New York: Routledge, 1996)

Earlier in I Love To You the phrase ‘I love you’ becomes a site to reflect upon relations of self and other and how, in particular, to cultivate relations that respect the irreducibility of two sexuate identities. She suggests phrases such as ‘I love to you’ could be used instead of ‘I love you’. In French ‘j’aime a toi’ could be used instead of ‘je t’aime’. In the phrase ‘I love to you’ the ‘to’ is the site of the non-reduction of the person addressed as ‘you’ to an object. ‘To’ maintains a mediation between two subjects. The verb ‘love’ is thus transformed from a transitive verb with a direct object, to an intransitive verb. This shift approaches a relation between ‘I’ and ‘you’ as two subjects, rather than a divide of subject and object. Along with this there is also a different temporality, a sense of non-immediacy that Irigaray is trying to conceive of.

This attention to temporality is potentially crucial for thinking about the moving image. What is more, we must pay attention to how the subject/object relations play out in language, for Irigaray’s rich philosophy seeks a space to refigure the terms of address and being with another. Attention to the girl in Irigaray’s project, therefore, gives us a useful way of approaching these poetic gestures on screen. Especially if we consider Irigaray suggestion that: ‘Poetic language sometimes keeps available a part of the energy of the coming into relation, and that of thinking when it exists.’ (Luce Irigaray, Way of Love, London and New York: Continuum, 2002, p.136)

Bibliography

Irigaray, Luce, I Love To You, London and New York: Routledge, 1996

Irigaray, Luce, Sexes and Genealogies New York, Columbia University Press, 1993

Irigaray, Luce, Way of Love, London and New York: Continuum, 2002