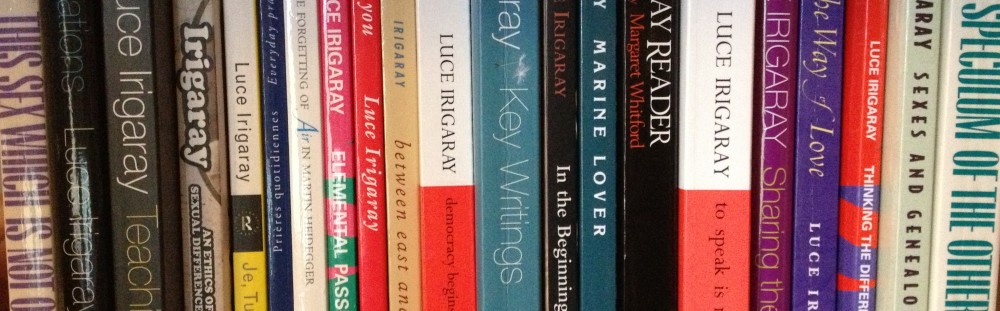

My thesis uses the notion of metamodernism and investigates the characteristics of this paradigm in relation with previous paradigms of thought, especially modernism and postmodernism. Metamodernism is defined from a variety of perspectives as a paradigm of integration: of faculties (reason and emotions), of systems of thought, of ontological levels, as exemplified in the poetry of William Blake and the denouement of Michel Tournier’s Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique. As Arundhati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things indicates, the contemporary metamodern paradigm is also a paradigm in which the disregarded ‘other’ is increasingly acknowledged and valued: women, the subaltern and the colonized, the innocent and the oppressed become central actants in the contemporary cultural discourse. This corresponds to a necessary cultural and personal transformation, as Luce Irigaray points out in Sharing the World and elsewhere. As a result, values that are essential to most religions and cultures, but which have been too often sidelined in (post)modernity, are increasingly revisited and redefined. Some of these values are innocence and the protection of the innocent and the disempowered, compassion, altruistic love, forgiveness, morality, respect for creativity and ingenuity.

My thesis suggests that a paradigm shift from (post)modernity to metamodernity is taking place. The emerging metamodern paradigm is one in which men and women ‘become themselves,’ as Irigaray puts it, as they engage in a dynamic evolutionary process, in which they take into account their difference and establish relations based on mutual reverence for their specific differences. The question of whether what Irigaray calls ‘becoming a whole self’ is comparable to a sublimation of the self, which Carl Gustav Jung has described as self-realization or individuation, remains open.

I link what Irigaray calls ‘becoming oneself’ with two main aspects of my thesis:

- A re-evaluation of the role of imagination and of what William Blake called ‘soft emotions’, considering them on a par with rationality, (Luce Irigaray, ‘Fecundity of Sexuate Art’ in Key Writings, p. 119)

- A ‘(re)discovery’ of women and of their part in bringing about cultural and social changes. This position is drawn from Irigaray’s affirmation of a double subjectivity and the importance of acknowledging the feminine as an other who is different.

I believe, with Irigaray, that one of the aspects missing from the construction of subjectivity in the Western culture is acknowledging the feminine. This acknowledgement is not always an easy task. It involves renouncing the primacy of the ego ‒ the masculine ego and the ego construed by women on its model ‒ and an opening towards the inside. This means engaging in one’s own inner becoming or personal evolution as a human being, as well as becoming open towards an outside other who is different from the self (Irigaray).

There is no doubt that women need to be valued for their proper qualities, rather than for their embodiment of the projections of the masculine psyche. But why value women? They enrich traditional masculine subjectivity, based on a rationalistic white culture (see Luce Irigaray, Sharing the World, p. 132). Women challenge the traditional ideal of a monolithic subjectivity by proposing another culture, a culture differently sexuated, something that can result in the self-centred masculine ego becoming more flexible and open up to a dialogue with the other, beginning with the feminine other.

Then a new human being appears who has shed the vestiges of conditionings, prejudice, desire for power and competition, and who focuses on his or her own becoming as a person, on accomplishing their potential as creatures whose strength is doubled by love and action inspired by contemplation. In my thesis, I explore how such transformations are enacted by the protagonists of William Blake’s Jerusalem, Michel Tournier’s Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique and Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. I study how, in these texts, the transformations of the self open up the possibilities of another age – the age of the breath and/or the age of the woman. As opposed to the glance which creates hierarchies by controlling, or looking up or down, the breath connects the subjects horizontally: it equalizes because it involves the sharing of the same air. In ‘Spirituality and Religion: Becoming Divine as Two,’(see Key Writings) Irigaray describes what could be a new stage in the evolution of our species:

Perhaps the best opportunity for a spiritual path today is to consider that we are in ‘The Age of the Breath.’ By cultivating breathing, we can gain an access to our autonomy, open a way for a new becoming and for sharing with other traditions. The breath exists before and beyond all representations, words, forms, all kinds of specific figurations or even idols, all sorts of rituals or dogmas, and thus allows a communication between cultures, sexes and generations. Breathing can create bridges between different people or cultures, respecting their diversities. (Key Writings, p. 146, emphasis is mine).

The women of such an age acknowledge and assume their difference(s) from men, their ‘autonomy’; they grow or ‘become’ continually, and they mediate or trigger the becoming of humankind. Becoming a spiritual personality – ‘becoming divine’ as Irigaray says – is open to individuals and to humankind as a whole, and it is predicated upon respect for difference(s). We are now ready, as Irigaray suggests, ‘to go from the most elementary of the survival to the most subtle of the spirituality’ (op. cit., p. 149).