In my thesis I investigate the political participation of children and their primary caregivers in the Platform of People Affected by Mortgages (short: PAH), a social movement defending the right to housing during the economic and political crisis in the Spanish state. My hope was to find inspiring forms of children’s political participation in the movement, as their voices in institutional participation structures are constrained by tokenism, discontinuity, and lack of accountability. I soon realized that I needed to go beyond the political theories I had studied up to that point to understand the generational order that prevents children from bringing something new into the world. I already had a deep understanding of the specific status of care in a political economy, but it wasn’t until I encountered the work of Luce Irigaray that I began to understand how the dynamics of a sacrificial economy, arising from an original matricide, hinders the becoming of children and their caregivers. My thesis is guided by one core argument: the political sphere rests on the invisible presence of the feminine-maternal – as a flesh of the flesh – and we could gain new insights into the social and symbolic positioning of the child if we dared to go back to encounter this first other.

Luce Irigaray detects a logic of sacrifice at the heart of Western culture which brings much of the cruelty and violence into the world. The social bond that constitutes this culture is built on the sacrifice of the maternal origin which positions the feminine-maternal as the infrastructure of symbolic exchanges. In her critique of psychoanalysis, Irigaray starts a dispute about questioning whether language can replace or acknowledge the absence of the m/other. She suggests that it is the denial of the maternal transcendence that confines the feminine to a maternal function when this absence – as an expression of a desire for a beyond of her love of her child – is staged as the child’s first step towards autonomy, as a first cultural achievement. The forgetting of the subject’s first dwelling has operated as the founding act of Western culture, which has constructed its language around a void: “Just as the scar of the navel is forgotten, so, correspondingly, a hole appears in the texture of the language” (Sexes and Genealogies, p. 16). Irigaray wonders whether this fundamental lack, which man orchestrates as his greatest loss and celebrates as the origin of his desire, does not in fact amount to a clandestine presence: “The father forbids any corps-a-corps with the mother. I am tempted to add: if only this were really true!” (Sexes and Genealogies, pp. 14-15). This controversy about the vacuity of the void has great significance for the analysis of the social organization of care. For it is only thanks to a maternal care, hidden beneath his discourse, that the subject can experience himself as autonomous without having to take charge of this autonomy by himself.

The, in fact masculine, subject is the master of time and writes history, while the feminine-maternal is degraded in his space (An Ethics of Sexual Difference, p. 7). In this economy of the Same, the child is placed as the past and the future of the subject. It is enveloped in his fantasies of immediacy and of immortality and it embodies the apparent innocence of the word. Irigaray describes the generational order as a kind of parody and farce regarding generation and genealogy, since the relations between the generations are structured inside the relationship of the subject with himself: “He is father, mother, and child(ren). And the relationships between them. He is masculine and feminine and the relationships between them. What mockery of generation, parody of copulation and genealogy” (Speculum, On the Other as Woman, p. 136). The degradation of the m/other in western cultures and societies to “a body uninhabited by self-knowledge” (And the One Doesn’t Stir without the Other, in Signs 7(1), p. 64) deprives the newcomers of the liveliness of their first world: “of the warmest and most vital childhood guidance: you-mommy” ( I Love To You. Sketch of a Possible Felicity in History, p. 119).

Luce Irigaray challenges the idea that a subject who neither speaks to his m/other nor cultivates his natural belonging, could bring something original to the world – as he is cut off from his own vitality. If patrilineal genealogy can be interpreted as the relations between the subject and himself, a coming into being of women and children can entail a reconfiguring of the concepts of form and matter as well as those of space and time. This reconfiguring must be established in consideration of the other who has still to be encountered. Such an encounter requires to respect difference, to share time and space, without appropriating or merging with the other: “Metaphysics seems to have been elaborated in order to allow us to escape an immediate nearness with another living being. It has not arrived at a point of constituting a dialectics of the relations with the other(s) in which touch itself would be the mediation. However, it is this mediation that we need in order to establish such a relational economy” (Sharing the World, p. 129).

The city, where presumed free citizens speak and act, is constitutively linked to the pre-political violence happening in the home, in which the m/other (and the colonized and exploited others) are in the service of its becoming. Irigaray argues that the phallogocentric erasure of human conception and birth prevents the recognition of alterity and constitutes the public world as a gathering of anonymous anyones, subjected to the Same and only the Same: “An unresolved link with the mother, an originary lack of recognition of her existence, irreducible to our own, leave us submerged in an undifferentiated collective ‘one’ in which each is confused with the other but without a possible meeting between us” (Sharing the World, p. 113). Irigaray suggests that the embodied child is only protected and can only move freely between intimate, public, and political space-times within a culture of sexuate difference: “Engendering a child is to be understood by the same measure as the engendering of society, History, and the universe. […] For such children, the body, the house, the public realm, are all inhabitable places. One passes over into the other without imperative” (I love to You. Sketch of a Possible Felicity in History, p. 30).

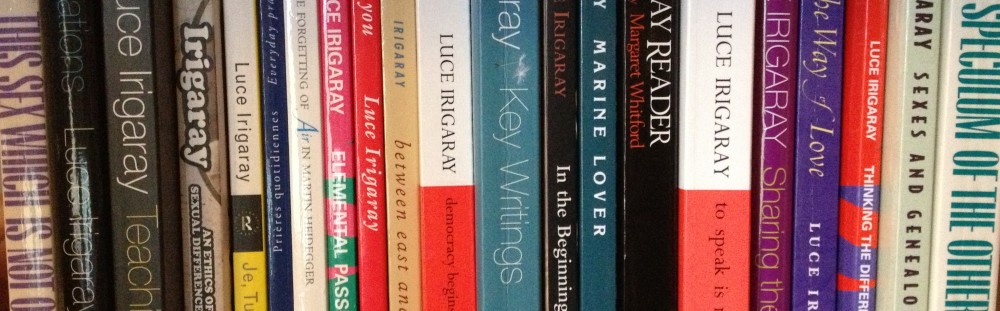

- Irigaray, Luce (1981): And the One Doesn’t Stir without the Other. In: Signs 7(1): 60-67.

- Irigaray, Luce (1985): Speculum of the Other Woman. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Irigaray, Luce (1993a): Sexes and Genealogies. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Irigaray, Luce (1993b): An Ethics of Sexual Difference. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Irigaray, Luce (1996): I Love To You. Sketch of a Possible Felicity in History. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

- Irigaray, Luce (2008): Sharing the World. London: Continuum.