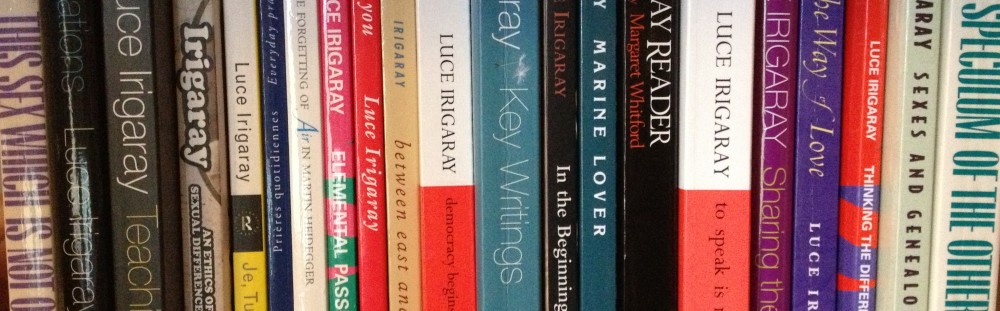

There is presently two main ways of understanding the term ‘Kathoey’ – กะเทย or Transgender woman. Some Kathoey feel proud to refer to themselves with this Thai term which has a long-lasting history, whereas others find the word Kathoey offensive. This different comprehension of the term urged me to discover the origin of its discriminatory meaning and ambivalent definition. In An Ethics of Sexual Difference, Luce Irigaray provides a clarification of her way of thinking which has been developed through her own experiences while also criticizing the masculine manner of producing knowledge. Following Irigaray, who guides here my way of learning, I will try to discover the meaning of Kathoey by returning to myself as becoming/being a Kathoey. Then, I will examine narratives in Buddhist literature to illustrate how Kathoey became ‘the other’, with a negative connotation, through a male knowledge production in order to understand the origin of its meaning.

1. What does Kathoey mean from my experience? Reading Irigaray’s philosophy compelled me to return to myself to rethink my experience of being and becoming Kathoey in Thai society. I remember Kathoey as the first term that has been imposed on me by society. The offensive character of the word made me feel shameful and created a feeling of being abnormal in my child-hood. Returning to Kathoey (myself) as an original local term and signification in the Thai language is a means of discovering how my self has been determined by Thai society and of deconstructing the negative connotation of the term Kathoey.

Applying Irigaray’s philosophical approach to Kathoey or transsexual/transgender experience, it is likely to concern oneself with sexual dimorphism. However, there is an argument in favour of ap-plying Irigaray philosophy to transsexual/transgender narrative. Poe (Can Luce Irigaray’s notion of sexual difference be applied to transsexual and transgender?) defends Irigaray’s ethics and argues that her ethics of sexual difference can apply to Transsexual/Transgender narratives. He read the culture of sexual difference as inclusive of transsexual and transgender experience (op.cit., p.116) and indicates that Irigaray’s thinking of sexual difference can help us to respect transsexuals and their relationship to nature and culture (op.cit., p.124).

For me, reading Irigaray’s work on sexual difference has been a help to balance my view on both sides: gender essentialism and sex essentialism. I live complex feelings regarding how I must position my subjectivity in the feminine spectrum. Claiming femininity makes difficult to avoid subjection to a biological essence but, on the other hand, trying to accept masculinity is truly unacceptable to my own feelings and experiences. Therefore, considering the Kathoey/trans subject as being irreducibly different might be a key to recognize its specificity in both views: a sex assigned by birth and a gender identification.

2. The origin of ambivalence and immorality reagarding Kathoey in Buddhist texts. The canon-ical scriptures of the Theravada Buddhism, describe the existence of four gender types which are listed as male, female, ubhatobyanjanaka, and bandaka. Ubhatobyanjanaka refers to those having characteristics of intersexed persons, while the definitions of Bandaka primarily refers to castrated men. Both terms have been expressed as Kathoey in the Thai translation of the Pali canon. Jackson (Male Homosexuality and Transgenderism in Thai Buddhist Tradition), provides an example of scriptural discrimination against Bandaka and Ubhatobyanjanaka through two significant stories in the Buddhist texts. One is the story about Phra Ananda and another is about Vakkali. As Jackson explains: ‘In previous existence Phra Ananda, the Buddha’s personal attendant, had been a gay or kathoey for many hundreds of lives. In his last life he was born as a full man who was ordained and was successful in achieving arahantship three months after the buddha attained nibbana. The reason he was born a kathoey was because in a previous life he had committed the sin of adultery. This led to him stewing in hell for tens of thousands of years. After he was freed from hell a portion of his old karma still remained and led to him being reborn as a Kathoey for many hundreds of lives ‘(Prasok, in Jackson, Male Homosexuality and Transgenderism in Thai Buddhist Tradition, p.72). And the second text is:’ Vakkali was the son of a Brahmin from Savitthi and was so impressed by the Buddha’s physical appearance that he sought ordination. But after being ordained he did not undertake the normal monastic activities, instead spending his time following the Buddha everywhere so that he could look at him. One day when Vakkali was staring unblinkingly at the Buddha, the Buddha castigated him, asking what he was looking for “in this stinking rotten body?’’. The Buddha then ordered Vakkali out of his presence. Vakkali was so shattered by this command that he attempted to kill himself by jumping off a mountain. But deva or spiritual beings informed the Buddha of Vakkali’s dejection quickly went to the monk’s aid in time to save him from committing suicide. With an extremely brief exposition of the dhamma, “The eyes see dhamma,” The Buddha gave Vakkali the insight he needed in order to attain the enlightenment and he immediately attained arahantship (Sathienpong, in Jackson, Male Homosexuality and Transgenderism in Thai Buddhist Tradition, p.74).

Even if these narratives show negative biases towards gender variant persons by characterizing them as being sinful and having extreme lust, they also provide a scriptural support to the possibility that sexual deviant or gender non-conforming persons might reach enlightenment by renouncing their sexual desires in the same way as male cisgender and heterosexuals. and they sug-gest that there is no difference spiritually. According to Irigaray’s ethics, erasing sexual difference and establishing a universal neutralized subject amounts to overlooking not only the differences between human beings but also the specificity of knowledge corresponding with the sex or gender. And yet it can be seen that a masculine knowledge and production is the cause of Theravada Bud-dhist rules and orders that still prioritize male cis/heterosexual norms, thereby contributes to the domination of the deviant with respect to them. Even the meaning of male/female and masculini-ty/femininity seems to be disrupted by the term ‘Kathoey’ in the Buddhist context and vice versa, since Kathoey as otherness still remains with a negative connotation.